From the Electrostatics

73. Electric field of evenly charged sphere and infinite plane

Spherical or close to spherical body shapes are widely spread in nature: stars, planets, rain drops, etc. And in the technique spherical bodies are often found. Flat surfaces also are frequently met. Besides, it is possible to consider very small area of any surface as flat. Therefore it is important to be able to determine the electric field of the sphere, charged uniformly on the surface, and the electric field of the evenly charged plane.

To find the field of a charged sphere or plane, you must mentally divide the body into such small elements that they can be considered as point charges. The strength of the point-charge field is known. Using the superposition principle, you can calculate the field strength at any point as the sum of the strengths created by the individual elements. In general, this problem is mathematically very complicated. For the sphere and the plane, finding the field is not difficult, because the field distribution in these cases has a simple symmetry. By using this symmetry, finding the field strength of field \(E\) can be greatly easier.

Consider a metal sphere of radius \(R_0\). Let the full charge of the sphere equal \(+q\). Because of symmetry of directions the charge is distributed on a surface of sphere uniformly. Hence, the charge falling on a unit of area (so-called surface density of charge sigma - \(\sigma\)),

\( \sigma ~= ~\frac{q}{A} \)

has the same value on all areas of the surface.

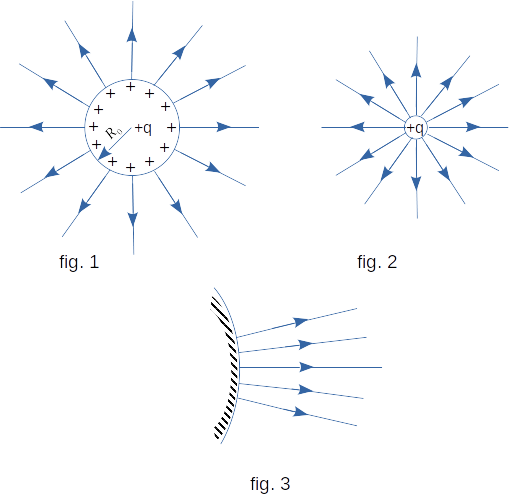

The power lines are perpendicular to the sphere surface and, if there are no other bodies near the sphere, in all points are directed along the extensions of the sphere radii (fig. 1).

Note that the distribution of power lines outside the sphere is the same as the distribution of point charge power lines \(+q\) (fig. 2). We are able to calculate the field of point charge. At distance \(R\) from the charge, the field strength in vacuum is equal to

\( E ~= ~\frac{q}{4 \pi \,\varepsilon{_0} \,R^2} \) (8-12)

If the patterns of power lines match, the field strengths must also match. Therefore, at a distance \(R\) (more than \(R_0\)) from the center of the sphere, the field strength of the charged sphere will also be determined by the formula \((8-12)\). On the same surface of the sphere, this strength is equal to

\( E_0 ~= ~\frac{q}{4 \pi \,\varepsilon{_0} \,R{^2_0}} \) (8-13)

The field strength of the sphere surface is very simply expressed through the surface charge density \(\sigma\). By substituting \(q\) in formula \((8-13)\)

\( q ~= ~\sigma \,A ~= ~\sigma \,\cdot \,4\pi \,R{^2_0}\)

we obtain

\( E ~= ~\frac{\sigma}{\varepsilon{_0}} \) (8-14)

With any \(R_0\), which means with \(R_0 ~\rightarrow ~\infty \), this formula is fair. But at very large \(R_0\), even significant areas of the sphere surface can be considered as flat. And the power lines of vector \(\overrightarrow{E}\) are perpendicular to the surface and practically parallel since the surface curvature is insignificant (fig. 3). That is why the electric field of a flat surface is uniform: decreasing the field strength with the distance from the charged surface can be neglected.

It means that the field of a conductor bounded by a flat surface is uniform and determined by the equation \((8-14)\). Inside the conductor, the field is zero. This allows us to find the field of the infinite charged plane.

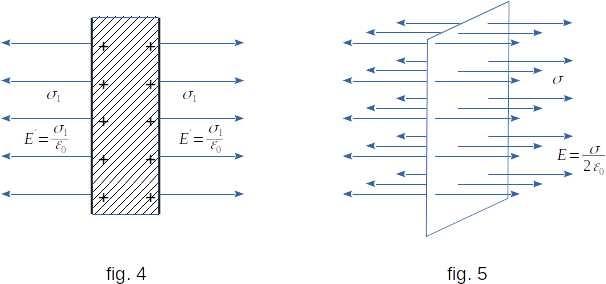

Let us first consider an infinite plane-parallel plate. Let it be uniformly charged and the surface density of charge \(\sigma{_1}\) is the same on both sides of the plate (fig. 4). The field created by the plate is uniform and its value on both sides of the plate according to definition \((8-14)\) is equal to

\( E\,^{'} ~= ~\frac{\sigma{_1}}{\varepsilon{_0}} \) (8-15)

We will reduce the thickness of the plate until both its surfaces are joined together. Then we shall receive the infinite plane with twice the big charge falling on unit of a surface: \(\sigma ~= ~2 \sigma{_1}\).

But the strength \(E\) of the field on both sides of the plane is still determined by the equation \((8-15)\)

\( E ~= ~\frac{\sigma{_1}}{\varepsilon{_0}} ~= ~\frac{\sigma}{2 \varepsilon{_0}} \) (8-16)

This is the result we are looking for: an infinite plane, charged uniformly with the surface density \(\sigma\), will create a uniform field whose value is determined by the equation (8-16). The power lines \(\overrightarrow{E}\) are perpendicular to the planes (fig. 5).

If the plane is surrounded by a uniform dielectric with dielectric constant \(\varepsilon\), the field strength will be \(\varepsilon\) times less

\( E ~= ~\frac{\sigma}{2 \,\varepsilon{_0} \,\varepsilon} \) (8-17)

In the CGSE system

\( E ~= ~\frac{2\pi \,\sigma}{\varepsilon} \) (8-18)

The infinite planes do not really exist. But if the dimensions of the plane are large compared to the distance from the given point, then the field strength at this point will be almost the same as from the infinite plane. After all, the remote areas of the plane have little effect on the field strength because the field strength from the small charge element decreases inversely proportional to the square of the distance.