From the Electrostatics

62. Electric charge and elementary particles

With the words "electricity", "electric charge", "electromagnetism" you have met many times and managed to get used to them. But try to answer the question "What is an electric charge?" and you'll see that it's not that easy.

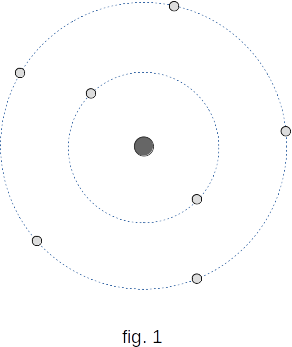

You can explain, for example, what an atom is, although it cannot be seen not only with a simple eye, but also with a microscope. In the centre of the atom there is a heavy nucleus, electrons move around it (fig. 1). But electric charge is something more primary than the atom. It is the simplest notion, not further divided into even simpler ones. Let's try to find out at first what is not an electric charge but what is understood by the statement: a given body or a particle has an electric charge. It's not exactly the same thing, and the last one is easier to understand.

You know that all bodies are built from the tiniest, indivisible already further on to simpler (as far as science knows now) particles, which for this reason are called elementary. All elementary particles have mass and thus are attracted to each other according to the law of gravitation with force inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

Most elementary particles, though not all of them, also have the ability to interact with each other with a force that also decreases inversely proportional to the square of the distance, but this force exceeds the gravitational force in a huge number of times. If particles are capable of such interactions, then it is said that particles have an electric charge. The interactions between charged particles themselves are called electromagnetic. In the hydrogen atom, for example, the electric force of attraction of the electron to the nucleus is \(10^{39}\) times greater than the force of gravitational attraction.

The presence of an electric charge at the particles does not mean anything else but their ability to electromagnetic interactions. Charge is a quantitative measure of the body's ability to electromagnetic interactions, just as the gravitational mass determines the intensity of gravitational interactions. Therefore, the charge of an elementary particle is not called a special "mechanism" in a particle that could be removed from it, decomposed into constituent parts and reassembled, but the ability of the particle in general to interact with other particles in a certain way. Accordingly there are particles without charge, but there is no charge without particle.

The presence of an electrical charge in the particles means that there are certain force interactions between them. But we essentially know nothing about the charge if we do not know the laws of these interactions. The knowledge of the laws of interactions must be part of our understanding of the charge. These laws are not simple, it is impossible to describe them in a few words. That is why we cannot give a sufficiently clear and brief definition of what electric charge is.

Two signs of electric charge.

In nature, there are particles with opposite charges. The charge of elementary particles - protons that are part of all atomic nuclei - is called positive, and the charge of electrons is called negative. A positive sign of a particle's charge, of course, does not mean that it has any special advantages. The introduction of charges of two signs reflects the fact that charged particles can either attract or repulse each other. At the same charge signs the particles are repulsed, at the different ones they are attracted.Elementary particle charge.

Besides electrons and protons, there are several types of charged elementary particles. But only electrons and protons can exist in the free state for unlimited time. The rest of the charged particles live no more than a millionth of a second. They are born in collisions of fast elementary particles and, having existed for very little time, decay into other particles. We'll learn about these particles in Book Four.Of the particles that do not have an electric charge, the neutron should be noted. Its mass is only slightly greater than the mass of the proton. Neutrons together with protons are part of the atomic nucleus.

So the elementary particle isn't necessarily charged. But if it has a charge, its quantity, as experience shows, is strictly defined. The charges of all elementary particles are the same in quantity and can only differ in signs. It is impossible to pinch a part of the charge, for example, from an electron. Why is it so, nobody knows yet.