From the interaction of atoms and molecules in substance

Mutual transformations of liquids and gases

43. Critical temperature

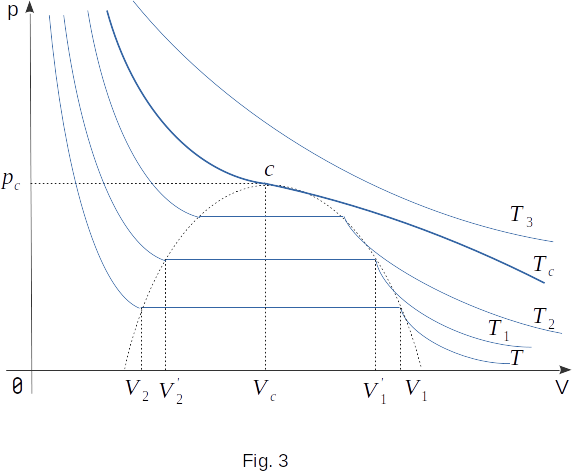

If several isotherms of real gas are constructed on the basis of experimental data (Fig. 3), a pattern common to all substances will be found. First, the higher the temperature, the lower the volume at which the gas condensation begins. Second, the higher the temperature, the greater the volume occupied by the liquid after all the gas has condensed. Consequently, the length of the straight section of the isotherm, corresponding to the equilibrium between liquid and gas, decreases with increasing temperature. Condensation begins at higher gas densities and ends at lower liquid densities. In other words, the higher the temperature, the closer the gas and liquid densities are to each other at the same pressure.

At sufficiently high temperatures, the horizontal part of the isotherm becomes very short, and at a certain temperature it becomes a point. This temperature is called critical. Each substance is characterized by its own critical temperature. For example, for carbon dioxide \((CO_2)\) the critical temperature is \(T_c \approx 31^0C\), and for water \(T_c \approx 374^0C\).

The state corresponding to the point to which the horizontal part of the isotherm is turned at \(T=T_c\) is called a critical state (critical point). The pressure in this state is also called critical. For carbon dioxide this pressure is \(73~atm\), and for water \(p_0 \approx 218~atm\). In the critical state, this mass of matter occupies a certain critical volume.

If the gas is compressed and the temperature is maintained at a critical point, its density will gradually increase until it reaches (in a critical state) the density of the liquid at the same temperature and pressure. With further compression, there will be one liquid in the cylinder under the piston. The transition of a substance from a gaseous state to a liquid at a critical temperature occurs smoothly and imperceptibly without the formation of a liquid-gas interface. There is no area in which the liquid and gas are in a state of equilibrium simultaneously. In the critical state, gas and liquid do not differ from each other.

To observe the critical state, let's take a transparent sealed container, the volume of which is equal to the critical volume for a given gas mass. Let's start heating the liquid in the container. As we approach the critical temperature, we can see how the liquid-vapor interface becomes weakly defined and unstable. In the critical state it disappears.

When cooling, a dense fog appears that fills the entire container. This produces droplets of liquid. They are then merged together and the interface between the liquid at the bottom and the vapour at the top appears again.

The best way to observe the described phenomena is to take the Ether, as it has a comparatively low critical pressure (about \(36 ~atm\)). Its critical temperature is also low: \(194^0C\).

At critical temperature the difference between gas and liquid disappears, and therefore the heat of vaporization becomes zero.

The table shows the critical temperatures of some substances found experimentally.

| Substance | Critical temperature, \(^0C\) |

|---|---|

| Helium | \(-268\) |

| Hydrogen | \(-240\) |

| Nitrogen | \(-147\) |

| Oxygen | \(-118\) |

| Chlorine | \(146\) |

| Ether | \(194\) |

| Mercury | \(1460\) |

Now, let's compress the gas, keeping the temperature above critical. Let's start with very large volumes as before.

A decrease in volume at a constant temperature greater than critical will result in an increase in pressure according to the ideal gas equation of state. However, if at temperatures below critical at a certain pressure condensation occurred, now the formation of liquid in the container is not observed at all. At temperatures above the critical gas can not be converted into a liquid at any pressure. This is the main meaning of the concept of critical temperature.