From the interaction of atoms and molecules in substance

Mutual transformations of liquids and gases

42. Real gas isotherms

In order to establish in more detail the conditions under which mutual conversions of gas and liquid are possible, it is not enough to simply observe the evaporation or boiling of the liquid. Changes in the pressure and volume of real gas at different temperatures must be carefully monitored.

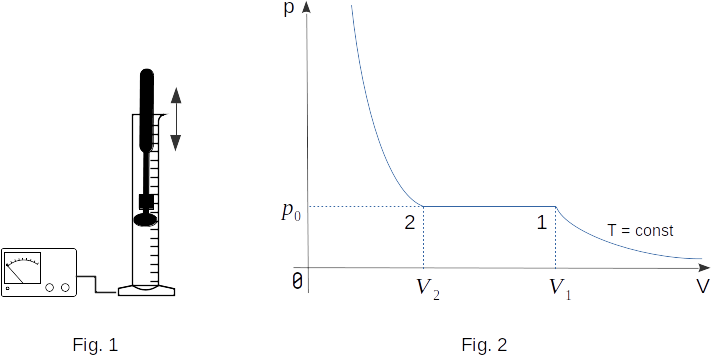

We will slowly compress the gas, for instance carbon dioxide, under the piston in cylinder (Fig. 1). By compressing the gas, we are performing work on it, so that the internal energy of the gas must increase. If the process is to be carried out at a constant temperature of \(T\), a good heat exchange between the cylinder and the environment must be ensured. For this purpose, the cylinder can be placed in a large container with a liquid at a constant temperature and the gas can be compressed so slowly that the heat can be transferred from the gas to the surrounding bodies.

Based on this experiment, it can be seen that, firstly, if the volume is large, the pressure with decreasing volume increases in accordance with the Boyle-Marriott law, and then, with the further increase in pressure, there are slight deviations from this law. Finally, starting with a certain value, the pressure does not change, despite the decrease in volume. If you look into the cylinder through a special viewing window, you can see transparent droplets on the walls of the cylinder and piston. This means that the gas has begun to condense, in other words, to become liquid.

By continuing to compress the cylinder contents, we will only increase the mass of the fluid under the piston and thus reduce the mass of the gas. The pressure shown by the pressure gauge will remain constant until the entire space under the piston is filled with liquid. Liquids are not compressible enough. Therefore, with further a slight decrease in volume does pressure increases very rapidly.

Since the whole process happens at a constant temperature \(T\), the curve showing the dependence of the pressure \(p\) on the volume \(V\) is called isotherm (Fig. 2). With the volume \(V_1\), gas condensation begins and with the volume \(V_2\), it ends. If \(V>V_1\), the substance is in a gaseous state, and at \(V < V2\) - in a liquid state.

Experiments show that all other gases have the same kind of isotherms, if their temperature is not too high.

The most remarkable thing about this process is the constant gas pressure when the volume changes from \(V_1\) to \(V_2\), when the gas is converted into a liquid. Each point in the straight section of the isotherm section \(1-2\) corresponds to the equilibrium between gaseous and liquid states of the substance. This means that the amount of liquid and gas above it remains constant at certain \(T\) and \(V\). As we already know, the equilibrium is dynamic: the number of molecules leaving the liquid is, on average, equal to the number of molecules passing from gas to liquid at the same time.

Constant pressure p, at which the liquid is in equilibrium with its gas, called the pressure of saturated vapour, and the gas itself, as previously mentioned, is called saturated vapour.

The independence of \(p_0\) from the volume is explained by the fact that as the volume of vapour decreases, most of it becomes liquid. And this mass of liquid is smaller than the same mass of gas. When the vapour is compressed over the liquid, the equilibrium is disturbed. The density of vapour at the first moment increases slightly and more molecules are transferred from gas to liquid than from liquid to gas. This continues until the equilibrium is re-established and the density and pressure are restored to their previous values.

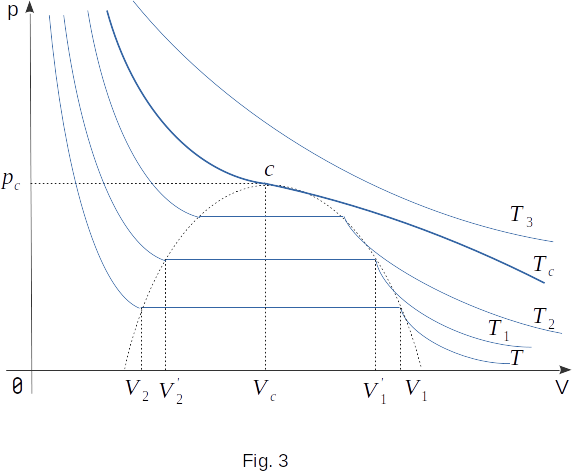

So far, we've only looked at one specific isotherm of real gas. Now let's see how carbon dioxide will behave at a different, higher (but also constant) temperature of \(T_1\). The new isotherm, like the old one, is pretty much the same as the isotherm of ideal gas at high volumes. Starting with a certain volume of \(V'_1 < V_1\), it also goes horizontally (Fig. 3). Finally, with a volume of \(V'_2 > V_2\), the isotherm goes steeply upwards. This means that with the volume of \(V'_2\) the whole cylinder is filled with liquid.