From the Electrical current in different environments

115. Electric current in semiconductors

In terms of electrical conductivity, semiconductors take an intermediate position between conductors and insulators. Since there is no sharp boundary between these three groups of substances, the question arises as to which of the three classes a substance should belong.

Semiconductors can be distinguished from conductors by the nature of the relationship between conductivity and temperature.

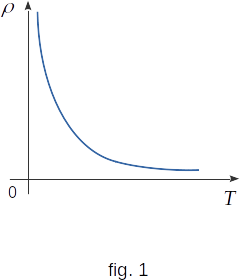

Measurements show that in a number of elements (silicon, germanium, selenium, etc.) and compounds (Pbs, CdS, etc.) the specific resistance does not increase with increasing temperature, as in metals, but, on the contrary, decreases (fig. 1). Such substances are called semiconductors. The graph in this figure shows that at temperatures close to absolute zero, the resistivity of such substances is practically infinite and, therefore, electrical conductivity is close to zero. This means that at such low temperatures, the semiconductor is actually a dielectric. As the temperature increases, the resistivity decreases rapidly. What's the reason for that?

The structure of a semiconductor.

To understand the mechanism of conductivity in semiconductors, you need to know the structure of semiconductor crystals and the nature of the bonds that hold the crystal atoms close to each other. For example, consider a silicon crystal.

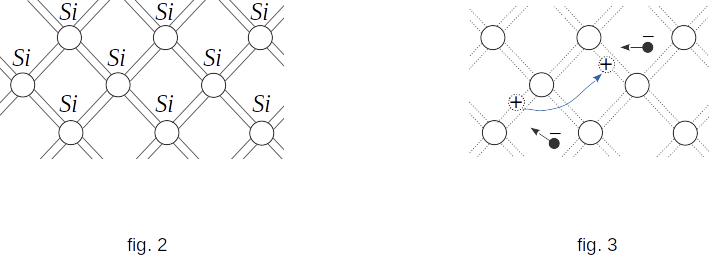

Silicon is a quadrivalent element. This means that in the outer shell of the atom there are four electrons, relatively weakly connected with the nucleus. The number of closest neighbours of each silicon atom is also four. The flat scheme of the structure of the silicon crystal is shown in figure 2.

The interaction of a pair of adjacent atoms is performed by a paired electron bond called a covalent bond. In the formation of this bond, one valence electron participates from each atom, which is detached from the atoms (collectivized by a crystal) and in its motion spend most of the time in the space between adjacent atoms. Their negative charge holds positive silicon ions next to each other.

One should not think that a collectivized pair of electrons belongs to only two atoms. Each atom forms four bonds with neighboring atoms, and this valence electron can move on either one of them. Having reached the neighboring atom, it can move to the next one and then further along the whole crystal. The collectivized valence electrons belong to the whole crystal.

The silicon paired electron bonds are strong enough and do not rupture at low temperatures. Silicon therefore does not conduct electrical current at low temperatures. The valence electrons involved in the bonding of atoms are firmly anchored in the crystal grid, and the external electrical field has no noticeable effect on their motion. A similar structure has a crystal germanium.

Electron conductivity.

When silicon is heated, the kinetic energy of the valence electrons increases and there is a rupture of individual bonds. Some electrons leave their "beaten paths" and become free, like the electrons in a metal. In the electric field they move between the nodes of the grid, forming an electric current (fig. 3).

The conductivity of semiconductors due to free electrons is called electronic conductivity. As the temperature rises, the number of broken bonds and thus free electrons increases. This leads to an increase in electrical conductivity and consequently to a decrease in resistance as the temperature rises.

Hole conductivity.

At broken bonds a vacant position with a missing electron is formed. It's called a hole. The hole has an excess positive charge in comparison with other normal bonds (fig. 3).

The position of the hole in the crystal is not constant. The following process is continuous. One of the electrons that provide the bonding of atoms, jumps to the place of the formed hole and restores the paired electron bond here. At the same time, a new hole is formed in the place where the electron jumped from. In this way, the hole can move around the entire crystal.

If the electric field strength in a crystal is equal to zero, the movement of holes, equivalent to the movement of positive charges, is chaotic and therefore does not create electrical current. If there is an electric field, the ordered movement of holes occurs and, therefore, to the electric current of free electrons is added electric current associated with the movement of holes. The direction of the holes movement is opposite to movement of electrons.

Since semiconductors have charge carriers of two types: electrons and holes, semiconductors therefore have not only electronic but also hole conductivity.