From the Electrical current in different environments

108. Non-independent and independent discharge

Non-independent discharge.

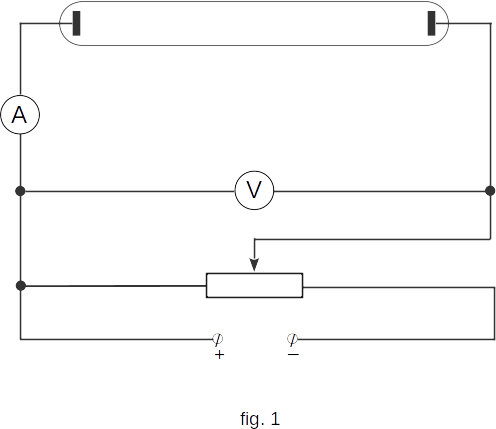

It is convenient to use a glass tube with two metal electrodes to study the discharge in gases at different potential differences (fig. 1).

With the help of an ionizer, such as X-rays, a certain number of pairs of charged particles: positive ions and electrons are formed in the gas in a time unit. If the potential difference on the electrodes of the tube is equal to zero, then the dynamic equilibrium is established in the tube, at which the number of newly formed pairs of ions will be equal to the number of ions pairs disappearing due to recombination.

At small potential difference between the electrodes of the tube positively charged ions move to the negative electrode, and negatively charged ions move to the positive electrode. As a result, an electric current is generated in the tube. The passage of electric current through gases is called a gas discharge.

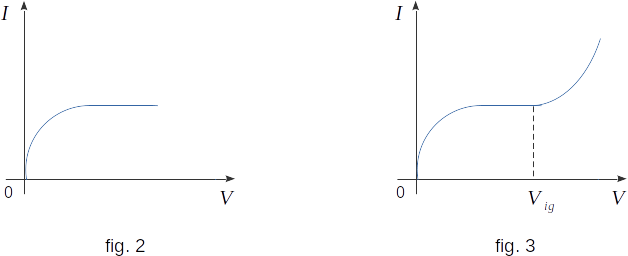

Not all of the forming ions reach the electrodes: some of them are reunited to form gas molecules. As the potential difference between the electrodes in the tube increases, the proportion of charged particles reaching the electrodes increases. The current in the circuit also increases. Finally, there comes a moment when all the charged particles formed in the gas volume reach the electrodes. At the same time, there is no further increase in electric current (fig. 2). Electric current, as we say, reaches saturation.

If the ionizer stops working, the discharge also stops, as there are no other sources of ions. For this reason, this discharge is called a non-independent discharge.

Independent discharge.

What will happen to the discharge in the gas if the potential difference on the electrodes continues to increase?

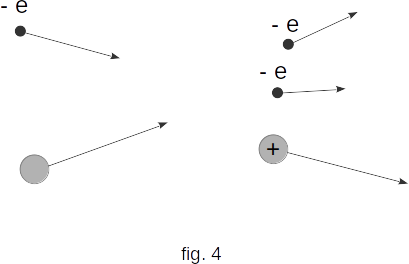

It would seem that the electric current should remain constant even if the potential difference continues to increase. However, experiment shows that if the potential difference between the electrodes increases, starting from a certain value, called the ignition potential \( (V_{ig})\), the electric current increases again (fig. 3). This means that there are additional ions in the gas above those produced by the ioniser. With a potential difference greater than \( V_{ig} ~\) the current can increase hundreds and thousands of times. Therefore, the number of ions formed is very large.

If you turn off the external ionizer, the discharge will not stop now. So, ions are formed by the processes occurring at the discharge itself. Since the discharge does not need an external ionizer for its maintenance, it is called an independent discharge.

Ionization by electronic shock.

Now let's explain the reasons for a rapid increase in electric current at high voltages.

Let us consider a pair of charged particles (positive ion and electron) formed by an external ionizer. The free electron that has appeared in this way begins to move to the positive electrode - the anode. On its way it meets ions and neutral atoms, i.e. it collides with them. In intervals between two consecutive collisions energy of the electron increases by work of electric field forces. The greater is the difference of potentials between the electrodes, the greater is the strength of the electric field. Kinetic energy of the electron before the next collision is proportional to the field strength and free path length of the electron (pathways between two consecutive collisions)

\(\frac{m\,\upsilon^2}{2} \,= \,e\,E\,l \) (10-12)

If the kinetic energy exceeds the work \(\, W_i ~\) which must be done to ionize the neutral atom, that is

\(\frac{m\,\upsilon^2}{2} \,\geqslant \,W_i \)

then in the collision of the electron with the atom ionization occurs. The scheme of this process is shown in figure 4. As a result, instead of one electron two electrons appear (one raiding the atom and being pulled out of the atom). These electrons in turn receive energy in the field and ionise the oncoming atoms, and so on. As a consequence, the number of charged particles grows rapidly, an electronic avalanche appears. The described process is called ionization by electronic shock.

However, a single ionization by electronic shock cannot provide maintenance of an independent discharge. Indeed, because all electrons appearing in this way are moving towards the anode and when the anode is reached, they leave the game. To maintain the discharge, new electrons must be emitted from the cathode. They can appear for two reasons.

Secondary electronic emission.

Positive ions formed during collisions of electrons with neutral atoms acquire large kinetic energy under the action of an electric field during their movement to the cathode. At impacts of such fast ions on the cathode electrons are kicked out of the cathode surface. This process is called secondary electron emission.

Thermoelectron emission.

In addition, the cathode can emit electrons when heated to a high temperature. This process is called thermoelectronic emission.

This process is explained as follows. When heated, the kinetic energy of both electrons and ions in the crystal grid increases. If accidentally one of the electrons acquires kinetic energy, which exceeds the energy of its connection with the crystal, it will leave the surface of the substance. Atoms (or ions) are more firmly connected with a piece of substance than electrons. Therefore, thermoelectronic emission occurs at lower temperatures than the vaporization of the substance.

When a cathode is discharged independently, it can be heated by bombarding it with positive ions. If the ion energy is not too high, there is no secondary electron emission and everything is limited to heating the cathode.