From the Electrical current in different environments

106. The Laws of Faraday

In studying the electrolysis phenomenon, Faraday established two laws.

Faraday's first law.

Let's denote in \(m\) the mass of the substance liberated at an electrode during the time \(t\), and in \(I\) - the force of electric current.

Measurements show that mass \(m\) is proportional to the force of electric current \(I\) and time:

\(m \,= \,k\,I\,t \) (10-8)

here \(k\) is the coefficient of proportionality, and \(~ I\,t \,= \,q ~\) is the charge carried by the ions during the time \(t\). From the equation \((10-8)\) it is seen that the coefficient \(k\) is numerically equal to the mass of the substance liberated at an electrodes during the transfer of ions of charge equal to \(1 \,q\). The value of \(k\) is called the electrochemical equivalent of this substance.

From the equation \((10-8)\) it follows that in SI units the coefficient \(k\) is measured in kilograms per Coulomb \((kg/q)\).

By measuring \(~m ~\) and \(~ q ~\), it is possible to determine the electrochemical equivalents of different substances.

The equation \((10-8)\) is expressed the Faraday's first law. The mechanism of ionic conductivity and electrolysis considered above in \( \S 105 \) helps to understand the meaning of Faraday's law. The more electricity passes through the electrolyte, the more ions will approach the electrodes and therefore the greater the mass of the substance will be liberated at them.

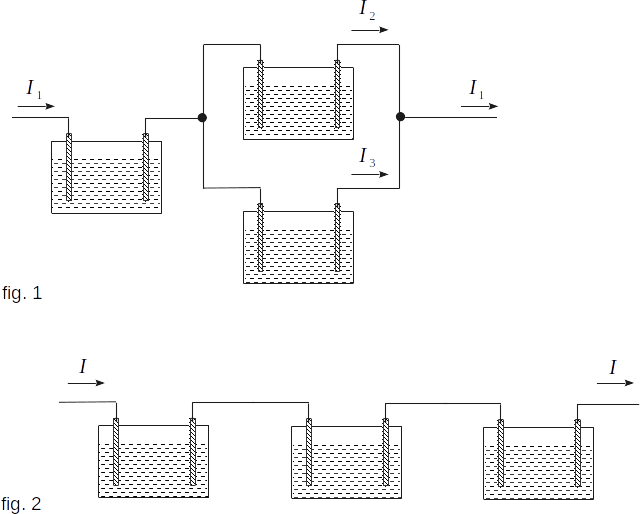

To make sure that the first Faraday law is fair, we can do the following. Let's assemble the installation shown in figure 1. All three electrolytic tubs are the same here, but the electric currents passing through them are different. Let's denote these electric currents through \(~ I_1, \,I_2, \,I_3\). Then \(~ I_1 \,= \,I_2 \,+ \,I_3\). Measuring the masses of \(~ m_1, \,m_2, \,m_3 ~\) of the same substance in different tubs we can see that they are proportional to the values of electric currents \(~ I_1, \,I_2, \,I_3\).

Faraday's Second Law.

The second Faraday law establishes the relationship of the electrochemical equivalent \(~k ~\) with the atomic mass and valence of atoms in dissociating molecules.

For example, atoms \(~ K ~\) (Potassium) and \(~ Br ~\) (Bromine) are single valence. As a result, the dissociation of the \(~ KBr ~\) molecule produces single-charged ions \(~ K^+ ~\) and \(~ Bg^- \).

In the \(~ CuSO_4 ~\) copper sulfate solution, two-charged \(~ Cu^{++} ~\) and \(~ SO^{--}_4 ~\) ions are produced during dissociation, since the copper atoms are bivalent.

Let us denote the valence of atoms \(~ z \), and the atomic mass \(~ M_a\). The ratio \(~ \frac{M_a}{z} ~\) is called the chemical equivalent.

Faraday's Second Law states that the ratio of electrochemical equivalent \(~ k ~\) to chemical equivalent \(~ (\frac{M_a}{z}) ~\) is constant. Let us denote this ratio as \(~ \frac{1}{F}\), then

\(k \,: \,\frac{M_a}{z} \,= \,\frac{1}{F} \) (10-9)

It is essential that the \(~ F ~\) value is a universal constant, i.e. it is the same for all substances. It is called the Faraday constant.

The meaning of the Faraday constant.

Let us put expression \((10-9)\) in equation \((10-8)\). As a result we get

\(m \,= \,\frac{1}{F}\,\frac{M_a}{z}\,I\,t \) (10-10)

Thus, the mass of the substance liberated at an electrode when the charge \(~ q=It ~\) passes is proportional to the chemical equivalent \(~ (\frac{M_a}{z}) ~\).

Let, for example, the mass \(~ m ~\), equal to \(~ (\frac{M_a}{z}) ~\), be liberated at an electrode. Let's find the necessary for this quantity of charge \(~ q \,= \,I\,t ~\). From the equation \((10-10)\) we obtain that \(~ F ~\) is numerically equal to \(~ q ~\).

Thus, the constant \(~ F ~\) is numerically equal to the charge, which must be passed through the electrolyte to liberate at the electrode mass of the substance, equal in grams to chemical equivalent (gram-equivalent).

The measurements showed that \(~ F \,= \,96\,500 \,q/g-eq, ~\) (coulomb/gram equivalent).

The second Faraday law can be checked using the setting shown in figure 2. Here, three electrolytic tubs with different electrolytes are connected in series, so the same charge \(~ q \,= \,I\,t ~\) flows through each tub for time \(~ t ~\). By measuring the masses of substances liberated at an electrodes it can be found that they are proportional to the corresponding chemical equivalents.