From the Electrical current in different environments

104. Molecular kinetic explanation of the Ohm's law

The observations described in the previous paragraph allow us to explain the main regularities of electric current passing in metals, which we know from the experiment. On this basis, we can derive, for example, the Ohm's law for a circuit section.

Let's show how to do it.

When a metal conductor is connected to a source of electromotive force (battery Volt for instance), an electric field with strength \(~ \overrightarrow{E} ~\) appears inside the conductor. Therefore, force will act on each electron

\( \overrightarrow{F} \,= \,-e\,\overrightarrow{E} \) (10-1)

As a result of this force, an ordered motion of electrons will be added to the chaotic motion. This creates an electric current.

What is the role of ions in the passage of electric current through the metal?

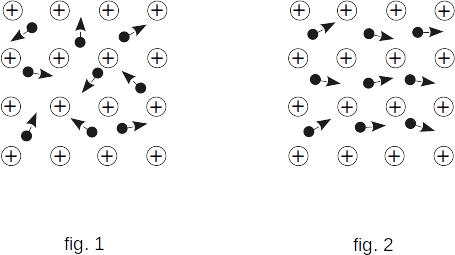

If the field strength \(~ \overrightarrow{E} ~\) is equal to zero, then motion of electrons is completely chaotic (fig. 1). At that average speed of electrons \(~ \overrightarrow{\upsilon}~\) is equal to zero and average kinetic energy is constant. It does not mean that kinetic energy of electrons does not change at interaction with ions. The change of energy occurs, and the kinetic energy of individual electrons can both increase and decrease. However, in average these changes are compensated and average kinetic energy of electrons remains constant.

Let now the strength of electric field \(~ \overrightarrow{E} ~\) be different from zero. Because of the action of force \(~ \overrightarrow{F} ~\) the electrons get acceleration in the direction of force action. The average speed of electrons becomes different from zero (fig. 2) and the average kinetic energy increases. When interacting with ions, electrons transfer to them a part of kinetic energy obtained by the work of force \(~ \overrightarrow{F} ~\). Loss of kinetic energy means that from the side of the ions a braking force \(~ \overrightarrow{f} ~\) acts on electrons, which can be called a friction force.

The force \(~ \overrightarrow{f} ~\) depends on the average speed of electrons \(~ \overrightarrow{\upsilon} ~\). The calculation shows that in metals the force of friction \(~ \overrightarrow{f} ~\) is proportional to the value of the speed and opposite to it in the direction

\( \overrightarrow{f} \,= \,-k\,\overrightarrow{\upsilon} \) (10-2)

where \(k\) is the constant value.If a direct current flows along the circuit, the average speed of electrons \(~ \overrightarrow{\upsilon} ~\) is also constant and the average acceleration is equal to zero. It means that the sum of average forces acting on electrons is equal to zero, i.e. \(\overrightarrow{F} \,+ \,\overrightarrow{f} \,= \,0\). Using equations \((10-1)\) and \((10-2)\) we find

\(-k\,\overrightarrow{\upsilon} \,- \,e\,\overrightarrow{E} \,= \,0 \)

from here

\( \overrightarrow{\upsilon} \,= \,-\frac{e}{k}\overrightarrow{E} \) (10-3)

The average speed of electrons in the metal is proportional to the electric field strength.

Let's remind, that density of an electric current \(~j ~\) is connected with average speed in equation

\(\overrightarrow{j} \,= \,-e\,n\,\overrightarrow{\upsilon} \) (10-4)

(here it is considered that \(q \,= -e\)).

Let's put expression \((10-3)\) for average velocity into equation \((10-4)\). As a result we obtain

\(\overrightarrow{j} \,= \,\lambda\,\overrightarrow{E} \) (10-5)

where\(\lambda \,= \frac{e^2\,n}{k} \) (10-6)

The density of electric current in the circuit is proportional to the electric field strength. The coefficient of proportionality is called specific electrical conductivity.

Let's show now, that from equality \((10-5)\) follows Ohm's law for a circuit section.

Let us consider for this purpose a piece of conductor in the form of a cylinder with length \(l\) (fig. 3) and cross-sectional area \(A\).

As vectors \(\overrightarrow{j}\) and \(\overrightarrow{E}\) are directed along the axis of the cylinder, the projection of the electric current density vector on the axis of the cylinder according to \((10-5)\) will be equal to

\(j \,= \,\lambda\,E \)

By multiplying this equality by \(A\) and considering that current force \(~I \,= \,j\,A\), we obtain

\(I \,= \lambda\,A\,E \,= \frac{A}{\rho}E \)

Here we have entered the designation \(~ \rho \,= \,\frac{1}{\lambda} ~\) for specific resistance.

Assuming that the uniform field strength is related to the potential difference \(~ \Delta{V} ~\) at the ends of the selected section by the ratio

\(E \,= \,\frac{\Delta{V}}{l} \)

we obtain the equation for \(~ I\)

\(I \,= \,\frac{\Delta{V}}{R} \)

where \(~ R \,= \,\frac{\rho\,l}{A} \,= \,\frac{l}{\lambda \,A} \)

This is Ohm's law for the section of the circuit.

Using equation \((10-6)\) for \(~ \lambda \), we can write down expressions for electrical resistance \(~ R ~\) and specific \(~ \rho ~\) as

\(R \,= \,\frac{l\,k}{A\,e^2\,n}, ~\rho \,= \,\frac{k}{e^2\,n} \) (10-7)

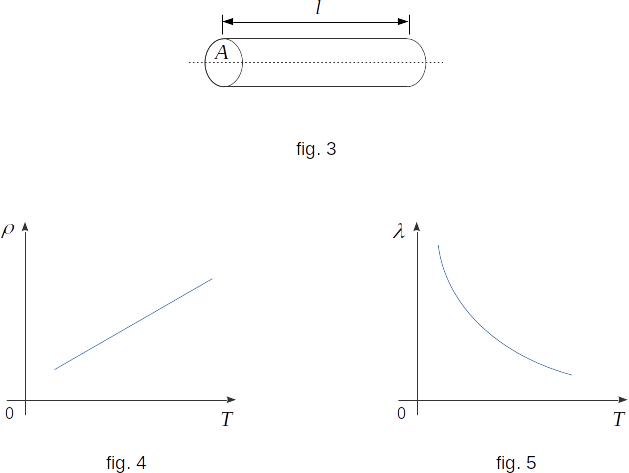

The value of the electrical resistance of metals depends on temperature (see \(\S\)93). In a wide temperature range, the specific resistance is proportional to temperature (fig. 4), and the electrical conductance is inversely proportional to temperature (fig. 5).

What is the reason for this \(~ \rho ~\) (or \(~ \lambda\)) temperature dependence?

In the equation \((10-7)\) for the specific resistance of the conductor value \(e\) is constant, so the change of \(~ \rho ~\) at heating can be caused by the dependence on the temperature of only two values: \(~ n ~\) and \(~ k \). In metals, the concentration of free electrons \(~ n ~\) at temperature change practically does not change, as "non-free" electrons are very strongly connected with ions.

The increase in resistance of metals with increasing temperature is caused by an increase in the coefficient of \(~ k ~\) at heating. The dependence of the coefficient \(~ k ~\) on temperature can only be obtained from quantum theory.