From the Direct electric current

100. The electromotive force of a galvanic element

Let's get familiar with the origin of electromotive force that occurs in galvanic elements. The easiest way to find out the basic principles of work of galvanic elements is to use the Daniel element as an example, although practically this element is not used at present.

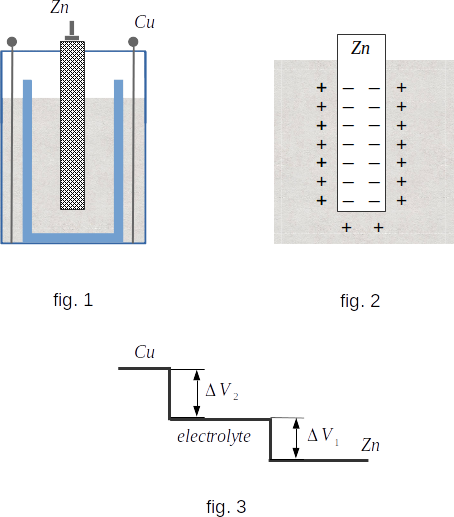

This is how it works. In a glass container is placed a glass of porous unfired clay (fig. 1). In the inner glass is poured aqueous solution of salt \(~ ZnSO_4 ~\) (zinc sulfate), and in the outer glass - copper sulfate solution \(~ CuSO_4\). Zinc and copper are used as electrodes. A porous wall prevents the rapid mixing of both electrolytes, but allows ions of different characters to seep in.

Let's see what happens to the zinc electrode first. If there was \(~ H_2SO_4 ~\) sulfuric acid in the inner container, a chemical reaction would start, as a result of which the zinc electrode would dissolve to form \(~ ZnSO_4 ~ \) salt. The same process would take place in the solution of zinc sulfate salt, if the concentration of zinc ions in it is not too high. And it is not neutral zinc atoms that pass into the solution, but its positive ions carrying a double elemental charge \((Zn++)\). This process is the result of chemical forces having an electromagnetic nature, but very complex in nature. We will not study the causes of chemical forces and the peculiarities of their action. The important thing is the following: the zinc electrode is negatively charged, because each leaving zinc atom leaves two of its electrons, and the electrolyte is positively charged. At the same time, the reverse process takes place. The zinc ion that takes part in the thermal motion of the electrolyte molecules can settle on the electrode again. After lowering of the zinc rod into the electrolyte in the time period the equilibrium state will be established, at which the number of zinc ions that left the electrode in the unit of time is equal to the number of ions that have settled down on it.

Find out the conditions for this equilibrium state to occur. As zinc dissolves between the electrode and the electrolyte there is an increasing potential difference, because zinc is negatively charged and the electrolyte is positively charged (fig. 2). Therefore, in a very thin layer of contact between electrode and electrolyte an electric field appears. This field prevents output of \(~ Zn++ ~\) ions from the electrode. Dissolution will stop when the force of the electric field becomes equal in value to the chemical force causing transition of \(~ Zn++ ~\) ions into solution. This chemical force in this case is an external force that drives the charged particles \(~ (Zn++ ions) ~\) and causes the appearance of electric current in the circuit. The equilibrium condition will be

\(E \,= \,-E_{ext} \)

where \(~ E_{ext} ~\) is the field strength of external forces of chemical origin.

The potential jump appeared at the boundary electrode - electrolyte depends on the available zinc ions concentration in the electrolyte. Experience shows that at normal concentration, when per one liter of solution there is one gram-equivalent of metal ions, potential difference between the electrode and the electrolyte

\(\Delta{V_1} \,= \,-0.5 \,v \)

(Gram-equivalent of the substance is called atomic mass divided by the valence of the atom).

Now let's see what happens to the copper electrode in copper sulfate solution. If the concentration of this solution is normal, then there is a reverse process: copper ions \(~ Cu++ ~\) are deposited on the electrode, charging it positively. And it continues until the potential jump of the electrode - electrolyte reaches the value

\(\Delta{V_2} \,= \,-0.61 \,v \)

As a result, the change of potential in the open element will have the form shown in fig. 3. Here it is considered that in the absence of electric current the potentials of both electrolytes are the same, because the electrolytes and the porous wall are conductors. The potential difference between the electrodes of the Daniel element at open circuit (it is equal to the element EMF) is

\(\mathcal{E} \,= \,\Delta{V_2} \,- \,\Delta{V_1} \,= \,1.11 \,v \)

if the concentrations of both electrolytes are normal.

Thus, the element EMF is equal to the sum of the potential jumps at the electrode - electrolyte boundaries. It does not depend on the electrode area and is determined only by the electrode material and the concentration of ions in the electrolytes. When moving a single positive charge inside the element from the zinc electrode to copper, external forces acting on the electrode - electrolyte boundaries will perform positive work. This work is equal to the sum of potential \(~ |\Delta{V_1}| \,+ \,|\Delta{V_2}| ~\) jumps, because chemical forces acting in the electrolyte layer adjacent to the electrode are equal in value to electrostatic ones.