From the Heat phenomena

13. Quantity of heat transferred

We can change the state of gas in the cylinder by simply heating it on the gas burner (Fig. 17). If the piston is fixed, the gas volume does not change, but the temperature and pressure increase. In this case, the condition changes without working on the gas. In this case, we can say that some quantity of heat is transferred to the system. This is the second way of changing the state of bodies.

The term "quantity of heat transferred" (or, in short, "quantity of heat") has arisen in those times when heat was considered as some undestroyable liquid - caloric, - capable to flow from a body with higher temperature to a body with lower temperature. It was believed that the more caloric in the body, the higher its temperature, and the quantity of heat transferred to the body was understood as the quantity of caloric flowing into it.

In reality, as we now know very well, there is no undestroyable liquid - caloric - that exists. Heating the body means increasing the speed of its molecules. When slower molecules of cold body interact with faster molecules of hot body on the edge of each body, the molecules work microscopically on each other. As a result, the speed of cold body molecules increases and the speed of hot body molecules decreases.

We are already familiar with the concept of heat quantity from the physics in the first book. But now this concept will be introduced more strictly. Just as the invention of the thermometer has made it possible to define temperature, the concept of the quantity of heat has acquired a precise meaning since the invention of the calorimeter, a device in which you can observe the heat transfer between bodies which are isolated from the interaction with the environment.

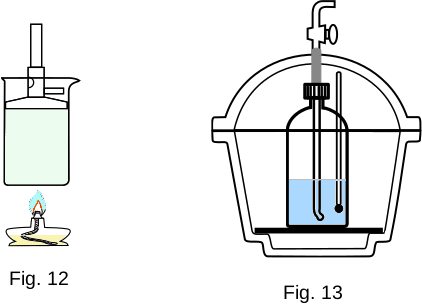

Let's take a large thin-walled metal container shaped like a cup. This container is placed on a stand inside another large container so that there is a layer of air between the containers. Cover both containers with a lid from above (Fig. 13). All this is a simple device and is a calorimeter. It is designed to minimise the heat exchange of the substance in the inner container with the environment.

Pour water into the calorimeter, the mass of which is \(m_1\) and temperature \(t_1\), then add water with the mass \(m_2\) and temperature \(t_2\). Let \(\,t_2 > t_1\). Heat exchange will start in the container and after some time the thermal equilibrium will be established - both portions of water will accept the same temperature \(t\). It is obvious that \(\,t_1 < t < t_2 \).

The change in the condition of both portions of water can be explained by the fact that the first portion received some heat and the second portion gave it away. Part of the heat will be transferred to the walls of the container itself. But if container mass is many times less than the masses \(m_1\) and \(m_2\), it is possible to neglect the heating of the container, without making a big mistake.

As you can see, the experience is very simple. But it took a lot of cleverness and perseverance to find out with the help of this and similar experiments the conservation of a new, previously unknown value. First of all, it was noticed that for the given water masses \(m_1\) and \(m_2\) at any initial temperature values \(t_1\) and \(t_2\) the ratio is remarkable in its simplicity

\( \frac{t -t_1}{t_2 - t} = \frac{m_2}{m_1} \) (1-15)

And note - no one knew in advance that any simple connection between temperature changes and masses should exist. Finding such simple connections is one of the sides of the scientist's talent. With a calorimeter, you can easily see for yourself the validity of the equation (1-15). This is, of course, much easier than opening this equation. It is essential that equation (1-15) is performed not only for water, but also for any liquid.

Now let's make the experiment harder. Instead of the second portion of water, we will put a piece of iron with a mass of \(m_2\), whose temperature is \(t_2 > t_1\), into the calorimeter. Over time, the equilibrium state will be restored. But the connection between temperatures and masses will be different. In the right part of the equation will appear the coefficient \(k\)

\( \frac{t -t_1}{t_2 - t} = {\frac{m_2}{m_1}}k \) (1-16)

This coefficient (it can be found by measuring t and knowing \(t_1, t_2, m_1, m_2\)) remains unchanged for this pair of substances at any mass and initial temperature. But if we take aluminum instead of iron or oil instead of water, the value of \(k\) will be different.

This allows us to conclude that the final temperature in the calorimeter depends not only on the masses of substances \(m_2\) and \(m_1\), but also on the specific thermal properties of these substances. This dependence is characterized by the coefficient \(k\).

For the same substances \(k = 1\), this coefficient can be written as a ratio of \(c_1\) and \(c_2\), characterizing the thermal properties of substances (for example, iron and water). Together with the mass ratio \(\frac{m_2}{m_1}\), the right side of the equation (1-16) should have the ratio \(\frac{c_2}{c_1}\), that is

\( k = \frac{c_2}{c_1} \) (1-17)

Let's name the change of water temperature \(\Delta t_1 = t - t_1 \), and the change of iron temperature \(\Delta t_2 = t - t_2 \) ( \(\Delta t_2 < 0\), if \(t_2 > t_1\) ), then the equation (1-16) can be written down in the form

\(\frac{\Delta t_1}{-\Delta t_2} = \frac{c_2m_2}{c_1m_1} \)

or

\(c_1m_1\Delta t_1 + c_2m_2\Delta t_2 = 0 \) (1-18)

Equation (1-18) has the character of a conservation law. The sum of two values, one of which refers to the first body and the second to the second body, is always equal to zero, regardless of the masses of the bodies, their temperatures and the choice of pairs of bodies. We chose water and iron randomly.

Let's name \(\Delta Q_1 = c_1m_1\Delta t_1\) the quantity of heat transferred to water, and \(\Delta Q_2 = c_2m_2\Delta t_2\) the quantity of heat transferred by iron. Then it can be claimed that the quantity of heat transferred in calorimetric experiments is conserved

\(\Delta Q_1 + \Delta Q_2 = 0 \)

Quantity of heat given away by one body is equal to quantity of heat received by the second body.

So, we have introduced a new value - Quantity of Heat: