From the Magnetic field of currents

129. Determination of the specific charge of an electron. Cyclic accelerator

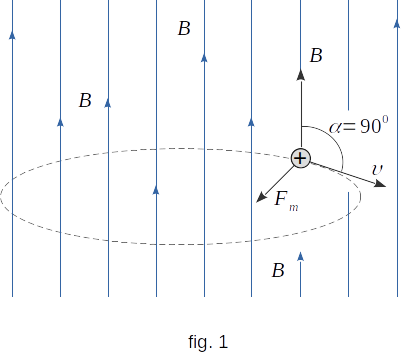

Lets examine the motion of a particle with a charge \(q\) in a uniform magnetic field \(\overrightarrow{B}\) directed perpendicularly to the initial velocity of the particle \(\overrightarrow{\upsilon}\) (fig. 1). As the Lorentz force is perpendicular to the particle velocity, this force does not perform the work. This means that the Lorentz force does not change the value of the Kinetic Energy of a particle, according to the kinetic energy theorem. The kinetic energy of a particle, and therefore the value of its velocity, remains constant. Force of Lorentz depends on velocity of a particle and on induction of a magnetic field. If velocity of a particle and induction of a field does not change then value of Lorentz force remains constant.

This force is perpendicular to the particle velocity and therefore determines the centripetal acceleration of the particle. The immutability of the centripetal acceleration module means that the particle moves uniformly around the radius circle \(r\). Let's define the radius. According to Newton's second law

\( m\frac{\upsilon^2}{r} \,= \,q\,\upsilon\,B \)

From here

\( r \,= \,\frac{m\,\upsilon}{q\,B} \) (11-5)

Therefore, by measuring \(\mathbf{r}\) and knowing the values of \(\mathbf{\upsilon}\) and \(\mathbf{B}\), we can measure the specific charge \(\mathbf{\frac{q}{m}}\) of different particles.

From equation \((11-5)\) we can see that the time of passage of a given particle of a semi-circle depends only on the properties of the particle and the magnitude of the magnetic field induction. In fact,

\( \Delta{t} \,= \,\frac{\pi\,r}{\upsilon} \,= \,\frac{\pi\,m}{q\,B} \)

This fact made it possible to create a device to accelerate charged particles with a relatively small electric field during a series of cycles - the so-called Cyclotron.

Excerpts from the centripetal acceleration.

\(\varphi=l/r=l'/R\)

\(\mathbf{\varphi=1}\) radian, a unit of angle between \(r\) and \(r'\) where \(r=l\).

\(l_{circle}=2\pi{r}\), \(~ \varphi_{circle}=2\pi \,rad. \approx 6.28 \,rad.\)

\(l=\varphi{r}\) and \(l=\upsilon{t} \,\rightarrow \,\upsilon{t}=\varphi{r}, \,\varphi=\upsilon{t}/{r}\)

\(\mathbf{\omega=\varphi/t=\upsilon{t}/r{t}=\upsilon/r}, \,~\mathbf{t=\varphi/\omega=\varphi{r}/\upsilon=2\pi{r}/\upsilon} \)

\(\mathbf{\Delta\overrightarrow{\upsilon}=\upsilon\varphi, ~~\overrightarrow{a}=\Delta\overrightarrow{\upsilon}/t=\upsilon\varphi/t=\upsilon\omega=\upsilon^2/r} \)

Accelerators. Cyclotron.

The operating principle of all Accelerators is simple - charged particles are accelerated by an electric field.

It is very difficult to create a potential difference of tens of megawolts, but it quickly became clear that this is not necessary. Instead, the accelerator can be rolled up into a ring by placing it in a magnetic field. Unlike the electric field, the magnetic field does not accelerate the particles, but only curves their trajectory. In particular, in a uniform magnetic field, the trajectory of a charged particle is encircled. If a particle is pushed forward by the electric field from time to time, particle will gain energy, gradually increasing the radius of the trajectory. In this case two problems are solved, the particle can be kept in orbit for as long as necessary, and the accelerating electric field does not have to be large (a thousand passes through the potential difference of one kilovolt is equivalent to a megavolt linear generator).

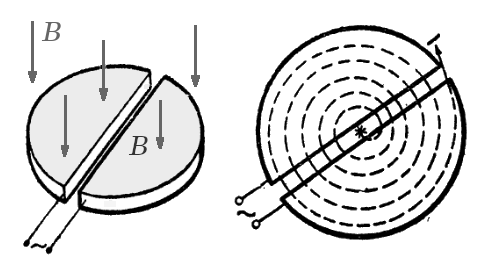

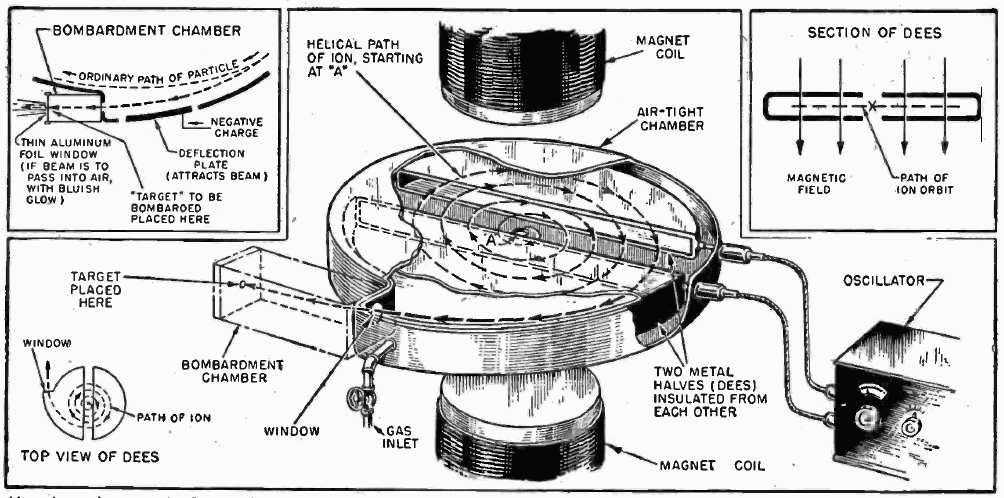

The cyclotron is designed as follows. Two hollow "D"-shaped sheet metal electrodes, called "dees", are located in a chamber where deep vacuum is maintained (fig. 2). The dees are placed face to face with a narrow gap between them, creating a cylindrical space within them for the particles to move. The particles are injected into the center of this space. The dees are located between the poles of a large electromagnet which applies a static magnetic field \(\overrightarrow{B}\) perpendicular to the electrode plane. The magnetic field causes the particles path to bend in a circle due to the Lorentz force perpendicular to their direction of motion.

If the particles' speeds were constant, they would travel in a circular path within the dees under the influence of the magnetic field. However a radio frequency (RF) alternating voltage of several thousand volts is applied between the dees. The voltage creates an oscillating electric field in the gap between the dees that accelerates the particles. The frequency is set so that the particles make one circuit during a single cycle of the voltage. Each time after the particles pass to the other dee electrode the polarity of the RF voltage reverses. Therefore, each time the particles cross the gap from one dee electrode to the other, the electric field is in the correct direction to accelerate them. The particles increasing speed due to these pushes causes them to move in a larger radius circle with each rotation, so the particles move in a spiral path outward from the center to the rim of the dees. When they reach the rim a small voltage on a metal plate deflects the beam so it exits the dees through a small gap between them, and hits a target located at the exit point at the rim of the chamber, or leaves the cyclotron through an evacuated beam tube to hit a remote target. Various materials may be used for the target, and the nuclear reactions due to the collisions will create secondary particles which may be guided outside of the cyclotron and into instruments for analysis.

Cyclotron Diagram

Why do we need an accelerator?

The accelerator is the sharpest microscope that scientists have at their fingertips. It allows them to see the smallest details of the substance's structure, which cannot be distinguished by any other means.

When we look at something with a normal microscope, we illuminate the object and observe it in diffuse light. But the microscope has a physical limitation: you cannot see objects as small as the wavelength of light. For visible light, it's about half a micron (\(1 \mu \,= \,10^{-6} \,m)\).

Electron microscopy makes it possible to distinguish smaller objects: instead of light, an object "illuminates" by a beam of electrons and observes how they scatter. The greater the energy of electrons, the smaller their wavelength, according to the laws of quantum mechanics, and thus the smaller details that can be seen. Electrons with energy of several kiloelectronvolts allow you to "see" separate large molecules, the atomic nucleus "visible" on the accelerator at the energy of electrons in the hundreds of megaelectronvolts, and the structure of the proton can be studied only after reaching the energy of about \(1 \,GeV\) (gigaelectronvolts).

Before that, physicists had studied the properties of those particles from which our world is directly composed - electrons, protons, neutrons. But having exceeded the energy of \(1 \,GeV\), physicists have discovered a new facet of our world, unknown before. Protons and neutrons began to break down, and new unstable particles were born and disintegrated in collisions. The higher the energy, the heavier and more remarkable the particles appeared.

Decades of research followed and it gradually became clear that it was impossible to understand our world by studying only electrons, protons and neutrons. Many unstable particles aren't "superfluous" at all. It turned out that they also define the structure of our "ordinary" world. The role of these particles is to be clarified in the future.

New accelerators are now being built precisely in order to study in detail the properties of heavy unstable particles. For example, the main task of the LHC (Large Hadron Collider) accelerator is to try to give birth and study the properties of Higgs boson and supersymmetric particles. This will be an extremely important step forward in understanding the phenomenon of our world. Test operation of the LHC began in September 2008 at the European Nuclear Laboratory.

Usage of accelerators and detectors in medicine

Of the approximately 17,000 existing accelerators, only about a hundred are used for scientific purposes. The rest are compact low-energy accelerators, half of which work for the benefit of medicine. They create short lived isotopes for accurate and, thanks to the ultra-low isotope concentration, safe diagnosis of diseases. And the low-dose digital X-ray units used in many dental practices are the descendants of the photon detectors used on the accelerators.

Many electron accelerators work as sources of synchrotron radiation - bright and narrowly directed X-rays, which "shine" electrons in the magnetic field. Such a ray is used both for diagnostics of diseases (for example, to obtain clear images of a network of small blood vessels) and for treatment.

Mass-Spectrometer

Another application of the magnetic field action was found in devices for determining the masses of atoms (molecules) by the motion character of their ions in electric and magnetic fields.

The neutral atom is not affected by the action of electric and magnetic fields. If, however, one or more electrons are taken away from it, or added to it, it will become an ion whose character of motion in these fields will be determined by its mass and charge. Strictly speaking, in Mass-Spectrometers not mass, but the ratio of mass to charge is determined. If the charge of a particle is known, the mass of the ion is definitely determined, and therefore the mass of the neutral atom and its nucleus. These devices are called Mass-Spectrometers.

By design, mass spectrometers may differ greatly from each other. They can use both static and variable in time fields, magnetic and/or electric.