From the Magnetic field of currents

126. Ampere's Force Law

A uniform magnetic field does not give acceleration to the frame with electric current. The frame only rotates in the magnetic field. This means that the forces applied to the different parts of the frame together give zero sum. However, the total cumulative momentum \(~ (p=m\upsilon) \,\) of these forces is different from zero, since the forces act at different points on the frame with current. Let us set what these forces are acting from the magnetic field side on a piece of conductor with an electric current.

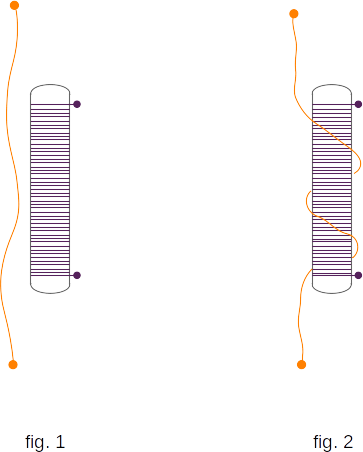

Let's do the following experiment. Hang the flexible conductor close to the vertically located solenoid (fig. 1). If the electric current passes through the solenoid, a magnetic field will appear around it. By passing the current through the conductor we will see that the conductor is winding on the solenoid (fig. 2). The upper end of the flexible conductor moves in one direction around the end of the solenoid, and the lower end around the other end of the solenoid moves in the opposite direction. If change the direction of electric current either in the conductor or in the solenoid, the conductor will unwinding, return to its original state and then is winding the solenoid but in the other direction.

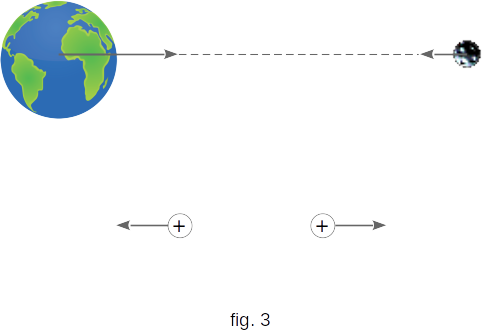

Magnetic interaction is a qualitatively different type of interaction compared to the known to us Coulomb and gravitational. The difference is that the forces arising from the Coulomb and gravitational interactions are central. These forces are directed along a line connecting the centers of interacting bodies (fig. 3).

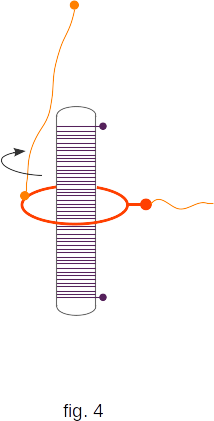

Forces of magnetic interaction have other character, distinctly visible on experiment with a flexible conductor. In the field of the magnet (or solenoid) the conductor rotates. And if an ongoing contact is made, for example, only with the upper half of the flexible conductor, the rotation would continue (fig. 4). This is the first time Faraday has done so. His installation was a kind of electric motor, in which the conductor with electric current, bypassing the solenoid on a closed circuit path, performed the work. Let us remember that the movement of the charge along a closed trajectory in the electrostatic field does not produce the work. The electrostatic field is a potential field.

The problem of determining the forces acting from the magnetic field on the conductor section with an electric current, was first solved by the outstanding French scientist Amper in 1820. Since it is impossible to create a separate current element, Amper performed experiments with large frame sizes as needed. By changing the shape of the frame and its location, Amper was able to mathematically calculate the force acting on a piece of conductor with an electric current in a magnetic field. It turned out that this force is proportional to the length of the piece of conductor and the force of electric current in it. The force also depends on the magnitude and direction of the induction vector of magnetic field \(~ \overrightarrow{B}\,\).

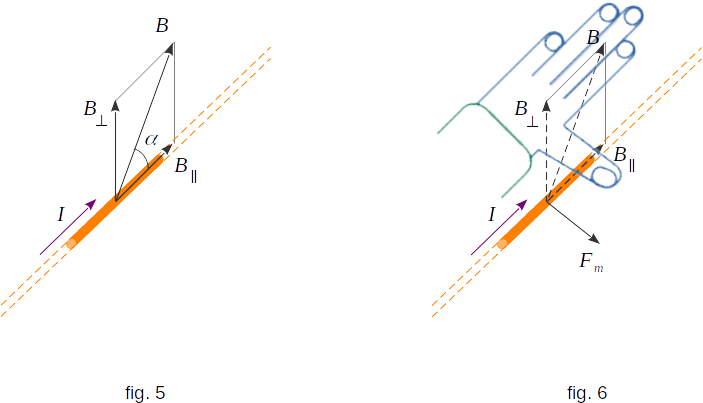

Let the angle \(\alpha\) be between vector \(~ \overrightarrow{B}\,\) and the direction of the conductor segment with current (current element) (fig. 5). (The direction of the current element is the direction in which electric current flows along the conductor). Experiment shows that the magnetic field directed along the conductor with electric current has no effect on the electric current. Therefore, the force depends only on the value of the component of vector \(~ \overrightarrow{B}\,\) which is perpendicular to the conductor, i.e. on the value \(~ B_{\perp} = B\,sin\alpha\). The final expression for force \(F\), acting on a small segment with the length \(\Delta l\) of the conductor with an electric current \(I\), from the side of the magnetic field \(~ \overrightarrow{B}\,\) having an angle \(\alpha\) with the conductor, will be

\( F_m \,= \,I\,\Delta{l}\,sin\alpha \) (11-2)

This equation is called the Ampere's Force Law.

Vector \(~ \overrightarrow{F}\) is perpendicular to the element with electric current and vector \(~ \overrightarrow{B}\,\) and directed to the side defined by the left hand rule. This rule, known from Physics Book One, is as follows.

If the left hand is positioned so that the perpendicular of magnetic field induction vector \(~ \overrightarrow{B}\,\) to the conductor enters in the palm and four extended fingers are directed along the current, then the thumb bent 90 degrees will show the direction of the force vector acting on a segment of the conductor (fig. 6).

The induction vector of the magnetic field \(~ \overrightarrow{B}\,\) is tangential to the induction lines (magnetic lines). Therefore, if the normal to the conductor which is the magnetic field induction vector \(~ \overrightarrow{B}\,\) enters the palm, then relative to the magnetic lines can also be said that they enter in the palm, though, perhaps, not at right angles.

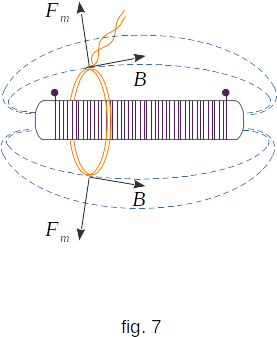

As an example of determining the direction of the Ampere's force, let us consider a long permanent magnet on which a much larger diameter coil is placed (fig. 7). If the coil is not exactly in the middle of the magnet, the magnetic induction vector \(~ \overrightarrow{B}\,\) is inclined towards the magnet at the points where the coil conductors are located but perpendicular to the coil conductors. Therefore, forces acting on current elements according to Ampere's Law stretch the coil and tend to drop it from the magnet. When the electric current changes direction, these forces, in contrast, compress the coil and tend to put it on the magnet.