From the Magnetic field of currents

123. Vector Induction of Magnetic Field

It follows from the previous paragraph 122 that the physical quantity characterizing the magnetic field must be vector. But what is this value?

Let's remember, what value characterizes an electric field. The ratio of force acting on a point test charge to the value of this charge (\(E=F/q\)) is taken to characterize the electric field. This ratio does not depend on the charge and therefore was used to characterize the field at a given point.

When studying the magnetic field, a small circuit (frame) with an electric current plays the role of the point charge. However, if the field within the frame can be considered equal, the total force acting on the frame from the magnetic field side will be equal to zero. The uniform magnetic field does not attract or repel the frame, nor does it accelerate in any other direction.

The forces acting on the frame only rotate it, i.e. they create a moment of force (torque) relative to some fixed axis. Experience shows that this torque depends on the location of the frame, its size (area) and the value of electric current flowing in it, but does not depend on the shape of the frame.

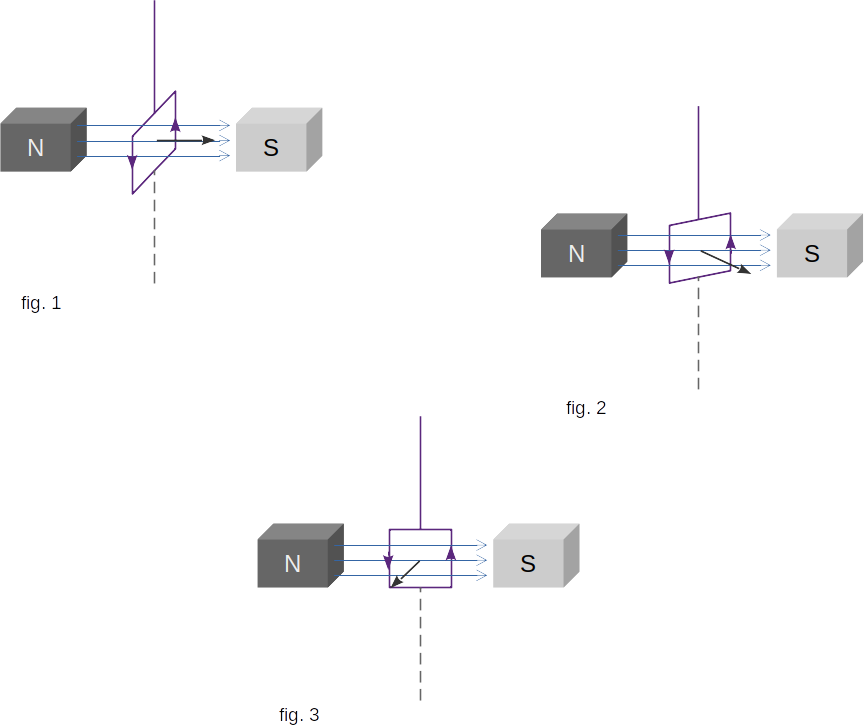

Let's take the frame with the area \(A\). Let the frame contain one coil of wire and the electric current \(\,I\,\) flows through it. Let us provide such a frame with a device allowing to measure the moment of forces (torque) applied to it. For example, let's hang the frame on an elastic thread, by the angle of winding of which you can judge the torque. Positioning the frame in different ways in the space where we want to determine the magnetic field, we will notice that the moment of forces acting on it changes. It is zero when the magnetic field is perpendicular to the plane of the frame (fig. 1). At other positions of the frame, the moment is different from zero (fig. 2). Turn the frame to find the position where the moment is the highest.

In this position, the normal \(~\overrightarrow{n}\,\) to the frame will be the right angle with the direction of the magnetic field (fig. 3).

The maximum moment of forces (torque) acting on the frame with electric current, \(\tau_{max}\,\) is proportional to the area \(~ A\,\) of the frame and to the current \(~ I\,\) in it:

\(\tau_{max} \,\sim \,I\,A \)

This basic experimental fact can be used to introduce the value characterizing the magnetic field in the place where the frame is located. Indeed, if the greatest moment is proportional to the electric current in the frame and its area, the ratio

\( B \,= \,\frac{\tau_{max}}{IA} \) (11-1)

does not depend on the properties of the frame and will therefore characterize the magnetic field at a given point in the space. This value is called magnetic field induction.

Earlier we found out that the magnetic field at each point has a certain direction. Let us give this direction to quantity \(~ B\), i.e. we will consider the magnetic induction as a vector whose direction coincides with the direction of normal \(~\overrightarrow{n}\).

The magnetic induction vector \(~\overrightarrow{B}\,\) fully characterizes the magnetic field. In each point its magnitude and direction can be found.

As a unit of magnetic induction in the International System of Units (SI), we take the magnetic induction of such a field, in which on the frame with the area of \(~ 1m^2\), with a force of electric current flows over it \(~ 1A\), the torque \(~ \tau_{max} \,= \,1 \,{N \cdot m} \,\) is acting.

\(1 \,unit ~of ~magnetic ~induction \,= \,1 \frac{N \cdot m}{A \cdot m^2} \,= \,1 \frac{N}{A \cdot m} \,= \,1T\)

The unit of magnetic induction was named "Tesla", in honor of inventor Nikola Tesla.