From the Molecular-kinetic theory of Ideal Gas

35. Brownian motion

The most convincing and visual proof of the fairness of molecular-kinetic theory was obtained in the study of Brownian motion. We have already mentioned it. The phenomenon of Brownian motion gives a rough, highly simplified, but deeply correct representation of the heat motion of molecules.

Its principle can be understood from the following simple example. Let's say two teams play soccer. But unlike ordinary soccer, there are not 11 players in the team, but a lot of them, so they fill almost the entire field. We are watching the field from such a distance that the eyes cannot distinguish between the individual running players. Under these conditions, instead of individual players on the field we will see a homogeneous surface. We could see more when playing not with a regular soccer ball, but with a large (three meters in diameter) lightweight ball. The ball will make random movements, as it is struck and pushed in different directions by players of fighting teams. The motion of the ball gives us a very simplified, rough picture of the continuous movement of players.

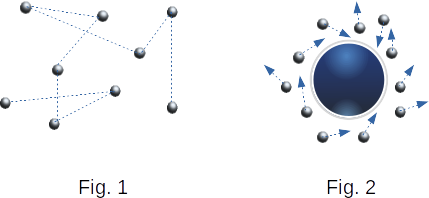

Similar actions are taken when observing Brownian motion. Only to help the eye take a microscope. A drop of liquid, to which added a small insoluble powder, is placed under the microscope lens. The English botanist Brown, who first observed this phenomenon in 1827, used the pollen grains. Nowadays, it is common to take paint particles of gummigut that are insoluble in water. These particles are constantly making a chaotic movement, which never stops. Its intensity increases with increasing temperature. Figure 1 shows the pattern of motion of the Brownian particle. Positions of the particle marked by dots are determined at regular intervals. These points are connected by straight lines. In fact, the particle trajectories between two successive collisions are much more complex.

Brownian motion can be seen in the gas as well. It is made by particles of dust or smoke suspended in the air.

The Brownian motion can be explained only on the basis of molecular-kinetic theory. The reason for the Brownian motion of a particle is that the strikes of a molecule against it do not compensate each other. Figure 2 schematically shows the position of one Brownian particle and its nearest molecules. Due to the chaotic movement of molecules, the momentum they transmit to the Brownian particle, for example, left and right, is not uniform. Therefore, the resulting pressure force is different from zero, which causes a change in the motion of the Brownian particle.

Average pressure has a certain value in both gas and liquid. But there are always minor random deviations from the average. The smaller the area of the body, the more significant these deviations of the pressure force acting on this area are. Thus, if the site has the size of several diameters of a molecule, the force acting on it changes in a jump from zero to some final value when a molecule enters this site.

The German physicist R. Paul colorfully describes the Brownian motion. Few phenomena are as fascinating to the observer as the Brownian motion. Here the observer is able to look behind the scenes of the nature. A new world opens up before him - the unstoppable hustle and bustle of a huge number of particles. The tiny particles quickly fly through the microscope, almost instantly changing the direction of motion. Larger particles are moving slowly, but they are constantly changing the direction of travel. Larger particles are practically pushed on the spot. Their protrusions clearly show the rotation of the particles around the axis, which constantly changes the direction in space. There is no sign of system or order anywhere. The dominance of blind chance is what a strong, overwhelming impression this picture has on the observer. No verbal description can even approximately replace one's own observation.

The Brownian Molecular Kinetic Theory was built by Albert Einstein in 1905. This theory was finally completed by the victory of the molecular-kinetic theory of substance structure. It was proved that Brownian particles participate in the heat motion of the environment: liquid or gas molecules. This proved the existence of molecules.

According to the equation \((3-12)\), the average kinetic energy of a particle's translational motion does not depend on its mass. In the case of a mixture of two gases, the average kinetic energy of each gas molecule is also determined by the equation \((3-12)\). If this were not the case, the temperatures of the gases would be different in the state of thermodynamic equilibrium, which is impossible.

The aggregate of Brownian particles can be considered as a gas, and, therefore, the average kinetic energy of the particle's translational motion is equal to

\(\frac{\overline{M\upsilon^2}}{2} ~= ~\frac{3}{2}kT \)

This equation explains why the intensity of Brownian motion increases with temperature and decreases with increasing particle mass. Because

\(\overline{\upsilon^2} ~= ~\frac{3kT}{M} \)

It should be said that it is complicated to measure experimentally the speed of the Brownian particle because of extreme irregularity of the Brownian motion.

If the mass of a particle is large, the average velocity of its motion will be so low that the particle's motion is almost impossible to detect.

The Brownian motion has practical meaning. Irregular oscillations of the arrows of sensitive analogue measuring instruments (Cavendish torsion balance for measuring the gravitational constant or high-sensitivity galvanometers) also represent Brownian motion. This imposes restrictions on the ability to increase the sensitivity of all measuring instruments at room temperatures. Only deep cooling makes it possible to increase the accuracy of measurements.