From the Molecular-kinetic theory of Ideal Gas

33. Gas molecule velocity measurement

If the average kinetic energy of the molecules is defined by the expression \((3-12)\), the average square of the velocity is equal to

\(\overline\upsilon^2 {~=~} \frac{3kT}{m} {~=~} \frac{3RT}{\mu} \)

since

\(k {~=~} \frac{R}{N_A}, {~\small{and}~} ~\mu {~=~} mN_A \)

from here, the average square velocity of the molecule

\(\overline\upsilon_{sq} {~=~} \sqrt{\overline\upsilon{^2}} {~=~} \sqrt{\frac{3RT}{\mu}} \)(3-13)

For nitrogen \(\mu ~= ~28 ~g/mol~ \) and at \(~t ~= ~0^0C, ~\overline\upsilon_{sq} ~\approx ~450 ~m/s\). Hydrogen at the same temperature has a velocity \(~\overline\upsilon_{sq} ~\approx ~1700 ~m/sec\).

When these numbers were first obtained (second half of the 20th century), many physicists were literally stunned. Calculated gas molecule velocities were higher than artillery bullets! Therefore, there were doubts about the fairness of the kinetic theory. After all, it is well known that the smell, for example, in the gas spread quite slowly, it takes about tens of seconds for the smell of perfume spilled in one corner of the room spread to another angle.

However, this contradiction can be easily resolved. It is necessary to consider the collisions of molecules, because of which the trajectory of each molecule is a very tangled broken line (Fig. 1). The molecule has high velocities in straight sections of broken line. Moving of the molecule is not significant on average, even during the time of the order of minutes, because the rectilinear parts of the trajectory are very small (about \(10^{-4} ~sm\) at atmospheric pressure). Experiments to determine the velocities of molecules proved the validity of the equation \((3-13)\).

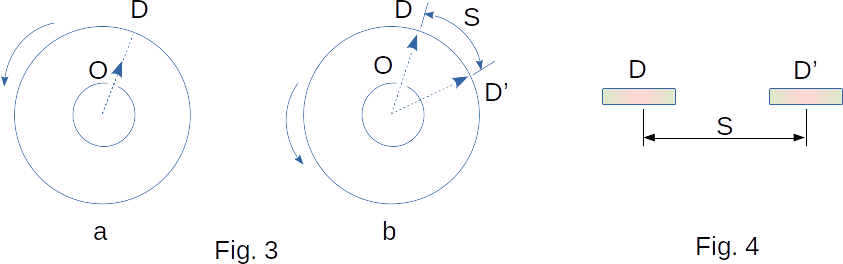

An elegant method of determining the velocities of atoms was proposed by Otto Stern in 1920. The device consists of two concentric cylinders \(A\) and \(B\), firmly connected with each other (Fig. 2-a). Cylinders can rotate at a constant angular velocity. Along the axis of the small cylinder there is a thin platinum wire \(C\), covered with a layer of silver. High electric current is passed through it. There is a narrow slot \(O\) in the wall of this cylinder. Cylinder \(B\) is located at room temperature.

At first, the device is not moving. When electric current flows along the wire, the silver layer evaporates and the inner cylinder is filled with gas from silver atoms. Some atoms fly through the slot \(O\) and, having reached the inner surface of cylinder \(B\), settle on it. As a result, a narrow strip of silver \(D\) is formed directly against the slot (Fig. 2-b). Then the cylinders are driven into rotation at a speed of \(~\omega\). Now for the time required by the atom to pass the path equal to the difference in radius of the cylinders \(R_b-R_a\), the cylinders will rotate at some angle \(~\phi\). As a result, atoms will fall on the inner surface of the large cylinder not directly against the slot \(O\), but at some distance \(S\) from the end of the radius passing through the middle of the slot (Fig. 3). After all, they move straight ahead. This distance \(S\) is equal to

\(S ~= ~\omega{R_b}\tau \)

where \(\tau\) is the time the atom goes through the path \(R_b-R_a\)

Obviously,

\(\tau ~= ~\frac{R_b-R_a}{\upsilon}\)

where \(\upsilon\) is atom velocity

Therefore,

\(S ~= ~\frac{\omega{R_b}(R_b-R_a)}{\upsilon} {~\small{and}} ~\upsilon ~= \frac{\omega{R_b}(R_b-R_a)}{S}\)

Knowing \(\omega, ~R_a {~\small{and}} ~R_b\) and measuring the displacement \(S\) of the silver band caused by the rotation of the device (Fig. 4), find the velocity of silver atoms. The values of speeds determined from the experiment coincide with the theoretical value of the average speed.