From the Thermal expansion of solid and liquid bodies

59. Thermal volume expansion

As at heating all linear sizes of a body increase, its volume should increase also.

Measurements show that within the limits of not so big interval of temperatures it is possible to consider that increase in body volume is proportional to temperature change. As well as at linear expansion, it is convenient to consider relative change of body volume \(\frac{\Delta{V}}{V_0}=\frac{V-V_0}{V_0}\). Relative change of volume is proportional to change of temperature

\( \frac{\Delta{V}}{V_0} ~= ~\beta{\Delta{t}} ~= ~\beta(t-t_0) \) (7-2)

The volume expansion coefficient \(\beta\), which shows how much the body volume will change if the body temperature changes by \(1^0{C}\), depends on the nature of the substance. The insignificant dependence of this coefficient on temperature can be neglected if the interval of temperature change is not very large. For most substances, the coefficient has the order of \(10^{-5} - 10^{-4} deg^{-1}\), which is very small.

If \(V_0\) is the initial volume at temperature \(t_0\), then the final volume is found by the equation

\( V ~= ~V_0(1 ~+ ~\beta{\Delta{t}}) \)

The linear expansion coefficient \(\alpha\) and volume expansion coefficient \(\beta\) are related. This relationship can be found by considering the thermal expansion of a simple body, such as a cube with an edge \(l_0\). When a cube heats up by \(\Delta{t}\), each side of the cube will increase by \(\Delta{l}\) and become equal to

\( l ~= ~l_0(1 ~+ ~\alpha{\Delta{t}}) \) (7-3)

The volume in this case equals

\( V ~= ~V_0(1 ~+ ~\beta{\Delta{t}}) \) (7-4)

But \(V_0 = l{^3_0}\) and \(V = l^3\). By putting \(l\) from \((7-3)\) into equation \((7-4)\), we get

\( \beta ~= ~3\alpha ~+ ~3\alpha{^2}\Delta{t} ~+ ~\alpha{^3}(\Delta{t})^2 \)

Since \(\alpha\) is very small, with small temperature changes, members \(3\alpha{^2}\Delta{t}\) and \(\alpha{^3}(\Delta{t})^2\) can be neglected compared to members \(3\alpha\). Therefore, \(\beta ~\approx ~3\alpha\).

Thermal volume expansion is observed in both solids and liquids. The liquids do not retain their shape, and therefore the concept of linear expansion does not apply to them.

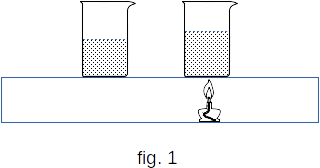

Changing the volume of liquid when heated in a container leads to an increase in liquid level, which can be measured (fig. 1). The volume expansion coefficients of liquids usually significantly above the volume expansion coefficients of solids, reaching values in the order of \(10^{-3} deg^{-1}\).

The most common liquid on Earth, water, has special properties in relation to thermal expansion. In contrast to other liquids, the volume of water when heated from \(0\) to \(4^0{C}\) does not increase, but decreases. Only starting from \(4^0{C}\) the volume of water starts to increase when heated. At \(4^0{C}\), the water volume is minimal and the density is maximum. This property of water has a great influence on the nature of heat exchange in water bodies. When water cools down, the density of the upper layers increases at first and they drop downwards. But after reaching a temperature of \(4^0{C}\), further cooling already reduces the density and cold layers of water remain on the surface. As a result, the water has a temperature of around \(4^0{C}\) even at very low air temperatures in deep pools.