From the Magnetic properties of the substance

146. The nature of ferromagnetism

Since ferromagnetics have much in common with paramagnetics (they magnetize in the direction of the field, turn into paramagnetics at sufficiently high temperatures), it is logical to assume that ferromagnetism is also a result of the orientation of currents in atoms in the external magnetic field. But it is necessary to explain why the orientation of currents is not destroyed by thermal motion, i.e. why there are permanent magnets. Next, we need to understand why even weak fields magnetise iron. Finally, why does hysteresis occur? There are many questions, and we can only answer them in general terms.

The facts that determine the properties of ferromagnetic substances.

First, ferromagnetism is not determined by the rotational motion of electrons around the nuclei, as was supposed at first, but by "their own rotation". The electron always seems to rotate around its own axis and, having a charge, creates a magnetic field along with the field appearing by orbital motion.

Adding "seems" to the word "rotates" is necessary because the electron does not look like a very small ball by its properties. Its motion is subject to the laws of quantum mechanics, not the classical Newton's mechanics.

The electron's own rotational moment is called the spin.

Secondly, between electrons under certain conditions determined by the structure of the atomic shell and the nature of the crystal structure of matter, there is a specific strong electrical interaction. If the energy of electrical interaction is greater than the energy of thermal motion of particles, then due to this interaction there appears a strictly defined orientation of electron spins. Only at temperatures above the Curie point does the thermal motion destroy this orientation.

Finally, the third most important fact. Under the influence of specific interaction of electrons, which was discussed, in non-magnetized substance appear areas of spontaneous (self-made) magnetization, so-called domains. In a domain, all spins are oriented in the same way and the magnetic fields created by electrons sum up, reinforcing each other. As a result, the domain is magnetized to saturation.

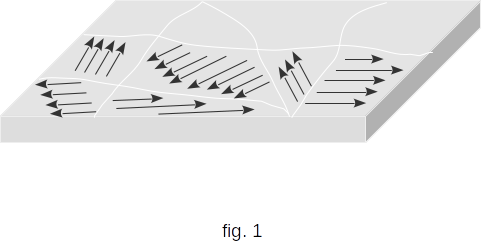

The orientation of spins and, accordingly, the direction of the magnetic field in different domains are different (fig. 1). Because of the chaotic distribution of field directions of individual domains, the body as a whole turns out to be non-magnetized, even though each domain is magnetized to saturation. The presence of domains is an essential feature of ferromagnetics. Domains can be observed directly with a microscope. If the smoothly polished surface of the ferromagnetic is covered with a thin ferromagnetic powder dissolved in liquid, this powder concentrates on the borders of domains. This happens because this is where the magnetic field changes with distance most quickly.

Magnetization of ferromagnetic is carried out by increasing the volume of domains magnetized along the external field, as well as changing the magnetization direction of individual domains. Orientation along the external field of magnetization of all domains can cause even relatively small fields. The whole sample turns into one big domain.

Orientation of large areas of domains, in contrast to the rotation of individual elementary electric currents occurs with friction and is therefore difficult. When an external field appears, all domains are not immediately magnetized along the field. The full magnetization orientation is achieved gradually as the field grows. This explains the nature of the magnetization curve shown in \(\,\S 145\,\) figure 1. As the magnetization field decreases, the disorientation of the magnetization of domains also occurs gradually. And because of the existence of friction, much of the domains remain magnetized in the same direction of magnetization. This results in a hysteresis and permanent magnets may exist.