From the Magnetic properties of the substance

143. Three classes of magnetic substances

When a piece of substance is placed in a magnetic field, the currents inside it are oriented in a certain way. The substance is magnetized, i.e. it creates its own magnetic field. In this case, the external magnetic field acts on the substance with a certain force. This force is the result of all elementary forces acting on individual currents occurring in the substance.

This force is determined by the magnetic permeability \(\mu\) of the substance. A small piece of substance is sufficient for this. However, the force acting on a substance, apart from the magnetic permeability \(\mu\), depends on the shape of the substance in a complex way. We will not consider this dependence on the shape in detail.

For us, it is important that such experiments make it possible to verify the existence of three classes of substances with sharply differing magnetic properties.

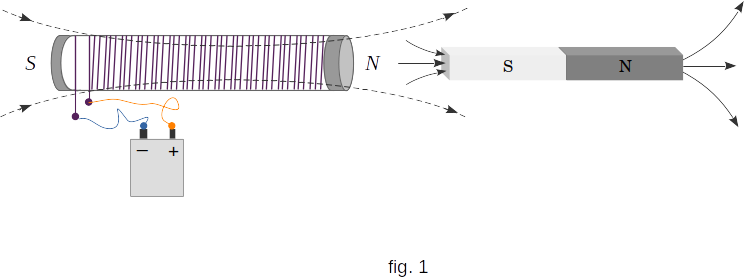

It is known that a piece of iron is attracted to a magnet or electromagnet. In other words, it moves to a place where there is magnetic induction. This happens because the elementary currents in the iron are oriented so that the direction of their field coincides with the direction of the magnetizing field. As a result, the iron rod turns into a magnet, the nearest pole of which is opposite to the pole of the electromagnet. Opposite poles of magnets are attracted (fig. 1). In other words, elementary currents in the iron rod are directed in the same direction as the current in the electromagnet winding. Identical directed currents are attracted, as it was seen from experiments.

Substances that, like iron, \(\mu>>1\), are called ferromagnetic. Besides iron, ferromagnetics are cobalt and nickel, as well as a number of rare earth elements and many alloys. The most important property of ferromagnetics is that they have residual magnetism. The ferromagnetic substance can be in a magnetized state and without an external magnetizing field.

The number of ferromagnetics in nature is relatively small. In most bodies, the magnetic properties are very weak. Their magnetic permeability is almost the same as in a vacuum with \(\mu \simeq 1\).

These substances with weakly expressed magnetic properties are divided into two classes. There are substances that behave in a magnetic field like iron, i.e. they are pulled into a magnetic field. These substances are called paramagnetic substances. Paramagnetics include sodium, potassium, manganese, aluminium, platinum, oxygen and many other elements as well as solutions of different salts.

Since paramagnetics are pulled into a field, the magnetic field they create is directed along the magnetizing field and amplifies it. So they have \(\mu > 1\). But it differs from the one \(\mu\) very little, only by an amount of about \(10^{-5} - 10^{-6}\). This is why powerful magnetic fields are required to observe paramagnetic phenomena.

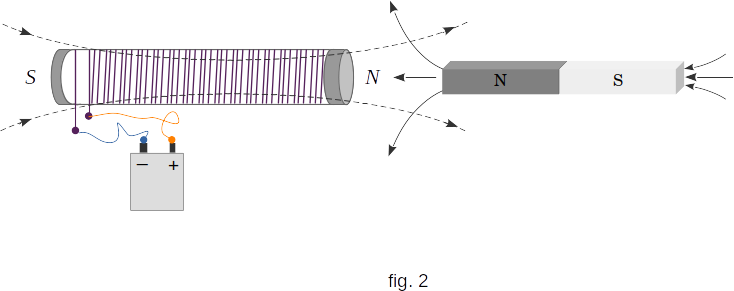

A special class of substances are the diamagnetics discovered by Faraday. They are pushed out from the magnetic field. If you hang a diamagnetic rod near the pole of a strong electromagnet, it will be pushed out of the pole of the magnet. Consequently, the field created by it is directed against the magnetizing field and weakens the field (fig. 2). Consequently, diamagnetics have \(\mu < 1\), and differ from one by an amount of about \(10^{-6}\).

Diamagnetics include bismuth, copper, sulfur, mercury, chlorine, inert gases and many other substances.