From the Molecular-kinetic theory

25. Structure of gaseous, liquid and solid bodies

With the help of molecular-kinetic theory we can understand why bodies are capable of being in gaseous, liquid and solid states.

Gases.

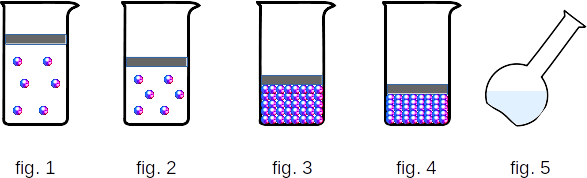

In gases, the distance between atoms or molecules is on average many times larger than the size of the molecules themselves (fig. 1). For example, at atmospheric pressure, the volume of the gas vessel is hundreds of thousands of times greater than the total volume of molecules. Molecules with high velocities move in space. Faced with each other, they bounce back from each other in different directions like billiard balls. The faster the gas molecules move, the higher its temperature.Gases are easily compressed, as only the average distance between the molecules decreases when the gas is compressed, but the molecules do not squeeze each other (fig. 2).

The weak attraction forces of molecules are not able to keep them close to each other. Therefore, gases can expand indefinitely. They do not only retain their shape as solids, but also their volume as liquids.

Countless hits of molecules against the vessel wall create gas pressure.

Liquids.

In liquids, the molecules are located almost closely together (fig. 3). Therefore, each molecule behaves differently than in gas. Clamped as "in a cage" by other molecules, it "runs in place" (fluctuates near the balance position). Only from time to time, she makes a "jump", breaking through the "bars of the cage", but immediately gets into a new "cage" formed by the new neighbors. The time of "sedentary life" molecule of water at room temperature, for example, continues about one hundred millionth fraction of a second, and the time for which one oscillation is made, much less (\(10^{-12} - 10^{-13} seconds\)). As the temperature rises, the time of "sedentary life" decreases. The nature of the molecular motion in liquids makes it possible to understand the main features a liquid's activity.The liquid molecules are close together. Therefore, when trying to change the volume of the liquid, even a small value begins to deform the molecules themselves (fig. 4). As a result, the liquid, unlike gas, is extremely difficult to compress. It is no more difficult to understand the reason for low compressibility of liquids than to understand why it is so difficult to squeeze into a crowded bus.

It is also clear why liquids flow, in other words, they do not retain their shape. Under the influence of an external force (usually a force of attraction to the Earth or a force of pressure from a moving solid body), molecules jump from one "settled" position to another mainly in the direction of force. That is why the liquid flows and takes the form of a vessel (fig. 5). The number of force jumps per second does not change significantly; it is determined by the intensity of the heat movement. For the flow of fluid it is necessary only that the time of action of force was many times longer than the time of "sedentary life" of the molecule. Otherwise, short-term force will only cause elastic deformation, and a drop of water will behave like a steel ball.

Solid bodies.

Atoms or molecules of solids, unlike liquids, cannot break their bonds with their nearest neighbors and fluctuate around certain equilibrium positions. Sometimes molecules change the position of equilibrium, but it is extremely rare. That's why solid bodies retain not only volume but also shape.

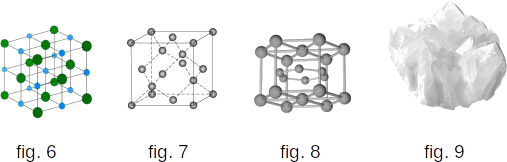

There's another difference between liquid and solid bodies. Liquids can be compared to a crowd in which people are restlessly pushed on the spot, and solid bodies are usually like a slender cohort (military unit of a Roman legion), where people keep certain intervals between them on average. If we connect the centers of the equilibrium of atoms or molecules of the solid body, we get the correct spatial structure, called the crystal structure. The figures show the crystal structure of table salt (fig. 6), diamond (fig. 7) and magnesium (fig. 8).

If nothing prevents the crystal from growing, the internal order in the arrangement of atoms leads to geometrically correct external forms (fig. 9).